In last week’s post we discussed how to create vector graphics from bitmaps in Inkscape. The third suggestion on why to do such a thing involved creating toolpaths for machines. As a natural continuation from last week, we’re now going to talk about such toolpaths, called G-code, and how to generate those in Inkscape.

What is G-code?

G-code is the most widely used programming language for controlling industrial machines such as mills, lathes and cutters as well as 3D-printers. G-code has many dialects or variants, but most (or all) adhere to certain common rules.

Structure and Commands

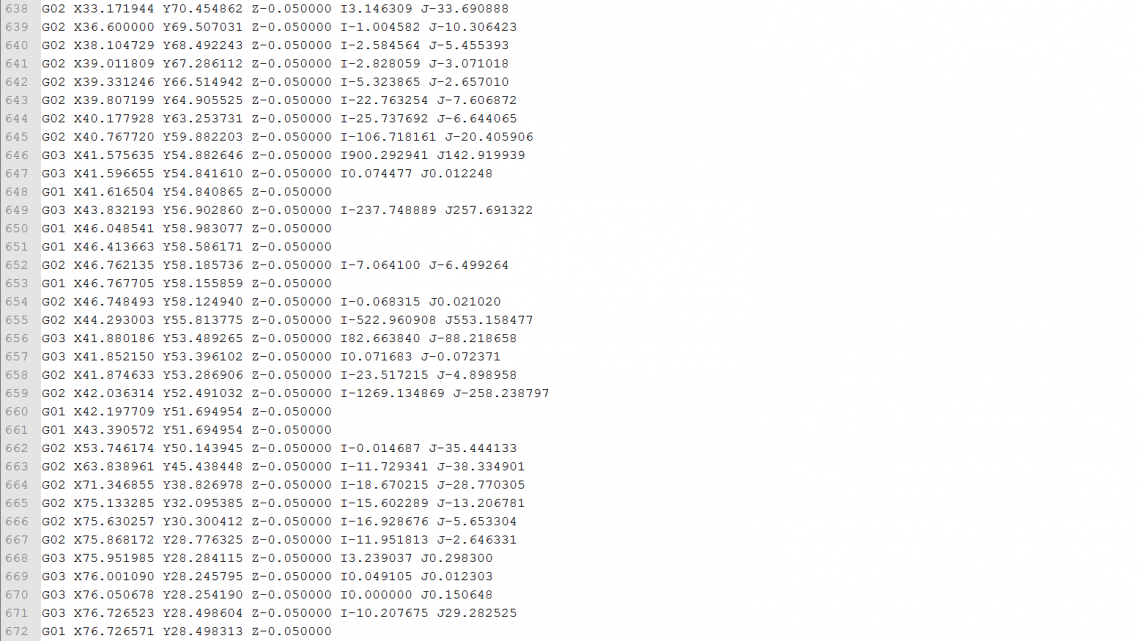

Each new line (called block) in the G-code can be roughly regarded as a new command. Everywhere you look in the code you will mostly see letters with numbers behind them. These letters corresponds to different types of commands. The most important ones are arguably G (used in most movement commands), M (miscellaneous commands), X, Y and Z (the last three are used to define positions in the X,Y,Z space, absolute or incremental). A complete list of all of the letters with explanations can be found here. A list of the different G and M-codes can be found here and here.

Example

A trivial example of a couple of blocks:

G90 G21 G00 X1.1 Y1.1 Z1.1 G01 Z-1.0 F100 G01 X2.2 Y3.3 Z-1.0 F500

The first block does two things and is kind of a very simple setup block. G90 is the command that defines all coordinates as absolute with an origin as a reference. G21 defines all numerical values as millimeters.

The second block makes the machine run rapidly to position (1.1,1.1,1.1) in the XYZ space from its current position. How fast this movement is done is defined in hardware.

The third block moves the machine in the Z-axis to -1 with a rate of 100 mm/min.

The last block moves the machine in a straight line to position (2.2,3.3) in the XY plane with a rate of 500 mm/min.

Generating G-code in Inkscape

Writing G-code manually for more than a simple square would be practically suicide, so luckily we have programs which do this for us.

Important Considerations!

When generating G-code this way it’s important to know what kind of machine you’re generating G-code for and how it interprets the code. Using Inkscape to generate G-code is NOT recommended when operating CNC mills, lathes, cutters or anything of that sort. For that it’s too dangerous! For those kind of machines you should use more professional software, such as anything from Vectric. However, if you’ve made a machine on your own which need some kind of motion, such as a drawing machine or a laser engraver, generating G-code in Inkscape is both quick and easy.

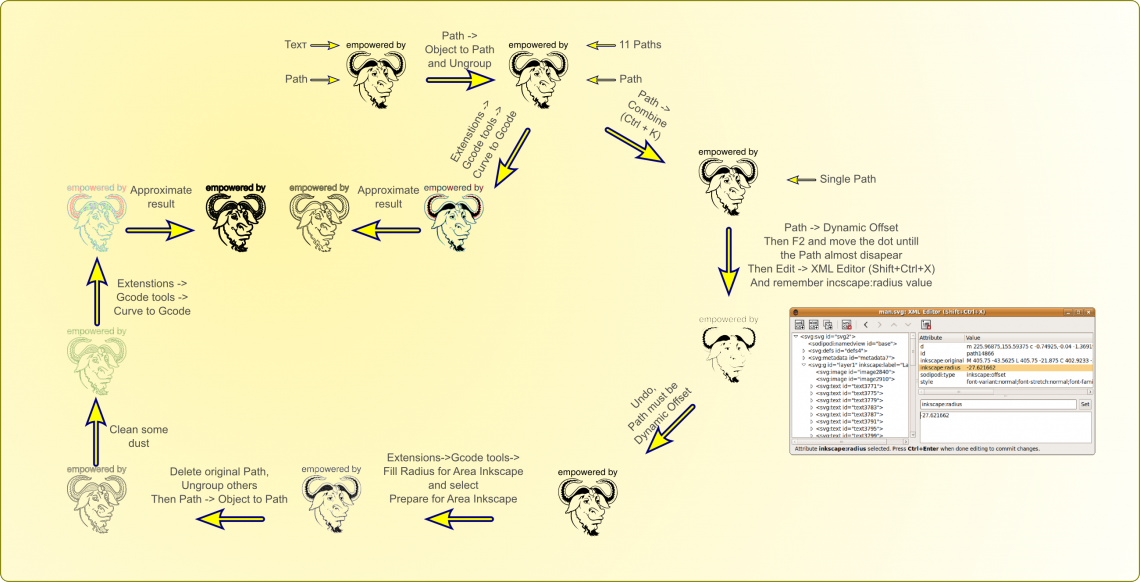

Gcodetools

You’ll need an extension (that’s what they call plugins in Inkscape) to be able generate G-code in Inkscape, and the only one that we’re aware of which is capable of doing so is Gcodetools (yes, this forum thread is the closest you’ll get an official page). It is far from perfect and poorly documented, but it does the job.

Step-by-step Tutorial (by example)

In this example we will generate a toolpath for our laser engraver to engrave a drawing of a dinosaur. The way the laser engraver interprets the G-code is that it turns on the laser when the virtual Z-axis has a negative value and off when it’s zero or positive.

Preparations

Edit February 2018:

First we follow the guidelines on Gcodetools’ page to install the extension. The gcodetools extension is now included in Inkscape’s default extension library. A dev version is also available from github if that’s what you prefer.

Since the drawing of the dinosaur is a regular bitmap image we need to trace the bitmap. Read this post to learn how to do this.

The object needs to be in an own layer (click the link to see how to use layers). Just cut-paste it into a new one to be sure.

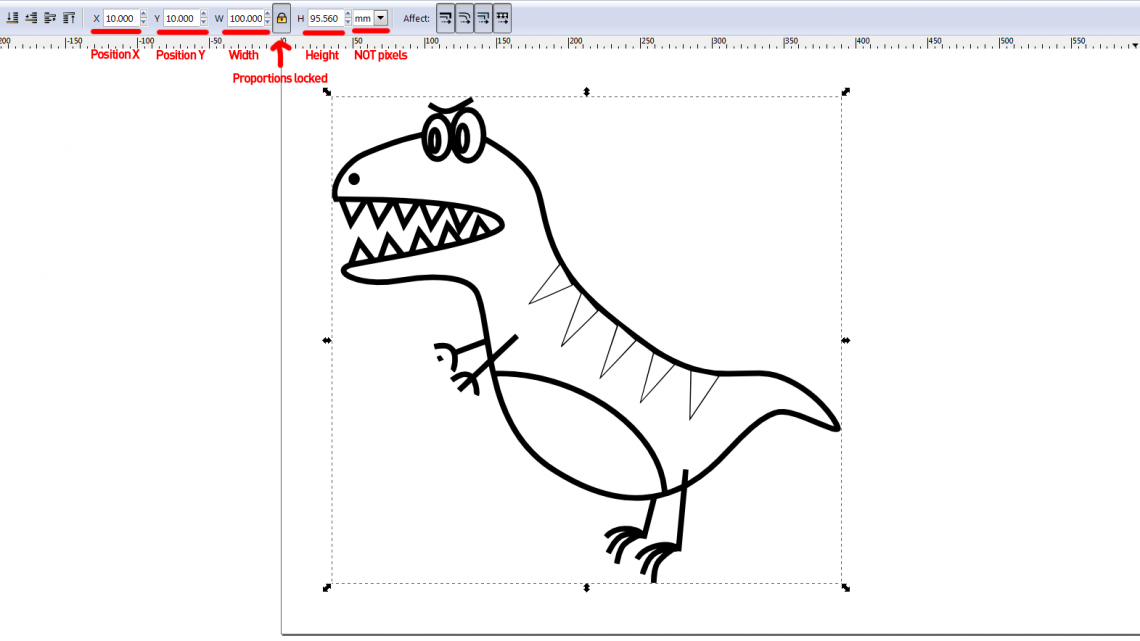

We want to have control of how large the result will be in real life. Therefore we scale the object such that it is as large as we want it in millimeters (click the padlock icon or hold ctrl down and drag a corner to lock proportions). In this example we want it to be maximum 100 mm in either axis. Also, we position the object where we want it. We want it to be at least 10 mm away from the X and Y axes.

If we select the object, we can see at the bottom of the Inkscape window how many nodes that exist along the path. We have a rule of thumb that it should stay below 3000 (or 10000 with only straight lines) so that the G-code generation won’t freeze up on us or take too long. If you have too many nodes, simplify the object by pressing ctrl+L as many times as necessary until the node count is low enough. Our dino is at 528 nodes, so we don’t have to simplify.

The Tools Library and the Green Thing

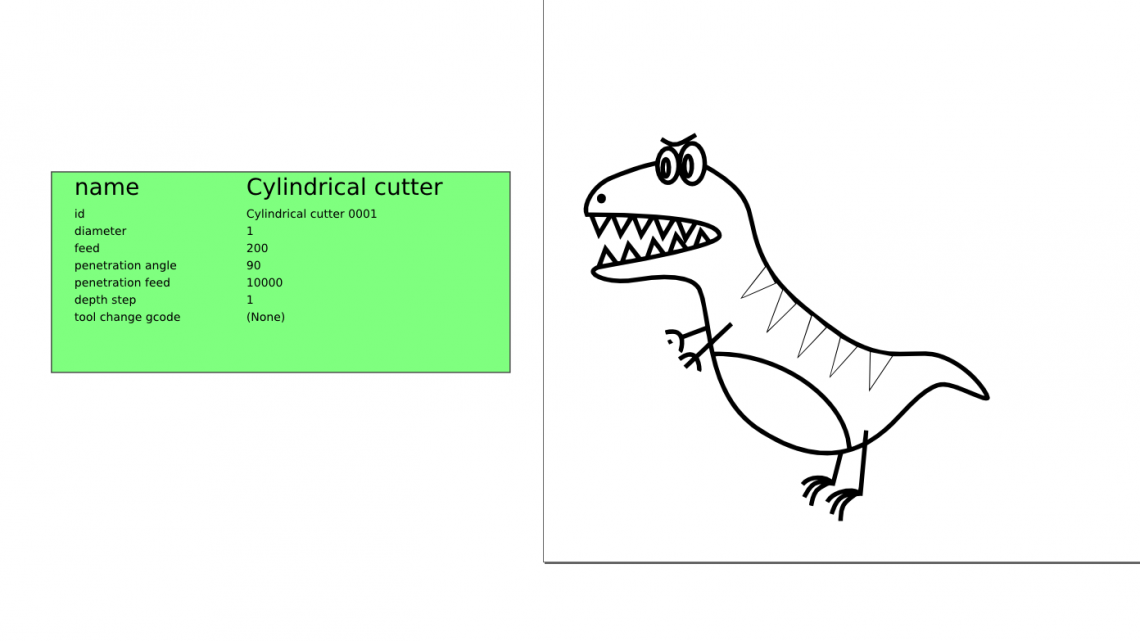

We need to choose a tool for the job, whether it’s our actual tool or just a virtual one. If we click the Extensions menu, and under Gcodetools we click Tools library…, we get to the window with the same name. In all our appliances for this type of G-code generation (laser engraver and plotter) we have used the cylinder option.

When pressing apply, an obnoxious green thing pops up in our drawing. We close the previous window and move the green thing away from obstructing our dino. This green square is part of the image and at the same time used to set up the G-code generation (weird, right!?).

To change the parameters, we select the text tool and click on the numbers. Let’s set the tool diameter to 1 (doesn’t have too much to say, but it’s best to not have it too big), the feed rate to 200 mm/min (in our case, this decides how strong the engraving will get) and the penetration feed to 10000 (just an arbitrary high number to quickly turn on and off the laser). We’ll leave the rest as it is.

Orientation points

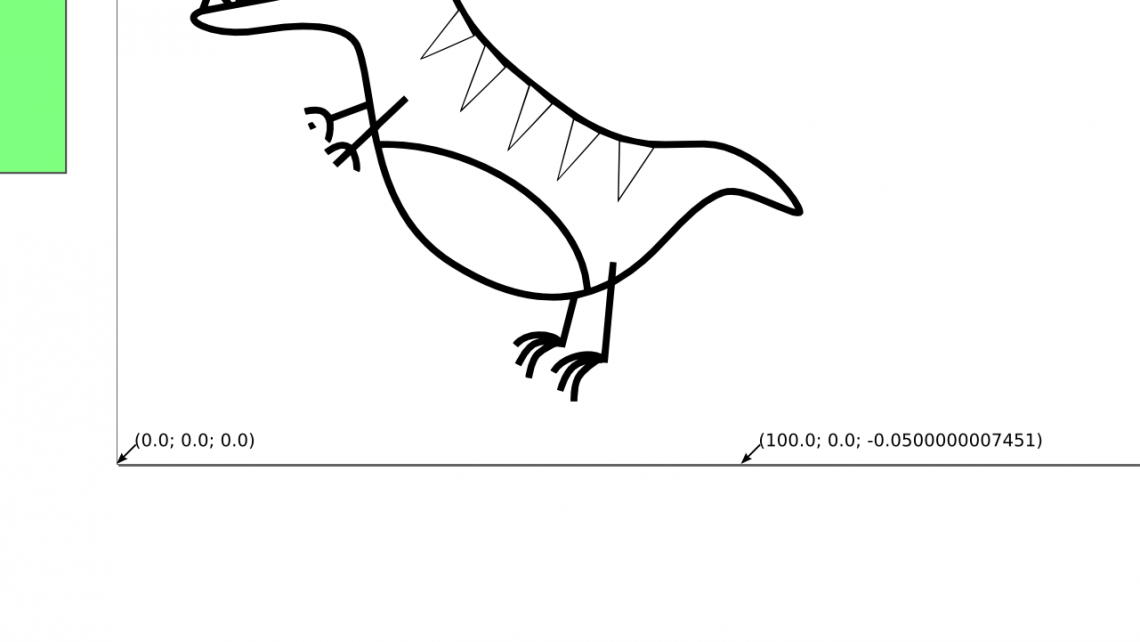

These are a bit cryptic, but we do need them. Select Orientation points… from the Gcodetools menu.

In the window that pops up we select the top option, set the Z surface to 0, the Z depth to -0.1 (we just want it to barely go below zero to turn on the laser quickly) and the Units as mm. Then we click apply and close the window. It is best to leave those arrows with the numbers in parenthesis that pop up where they are and don’t mess around with them.

Path to Gcode

Now we are ready for the magic. In the Gcodetools menu we select Path to Gcode….There are four tabs in the window that pops up.

We start in the Preferences tab. We name the file dino.ngc and places it in a convenient directory (e.g. C:\Users\Mads\Desktop). We set a low safe height such as 0.1 since we’re not actually moving along the Z-axis at all. Units: mm and Post-processor: None. The rest is blank.

Under Options we leave everything as they are by default.

In the Path to Gcode tab we make sure Subpath by subpath is selected and that Sort paths to reduse (yeah, we know) rapid distance is checked. The rest is as it is by default. Make sure that only the object you want to generate G-code of is selected (in our case: the dinosaur) and make also sure that you have the Path to Gcode tab selected before pressing apply (you will, believe it or not, get an error message if you have a different tab selected).

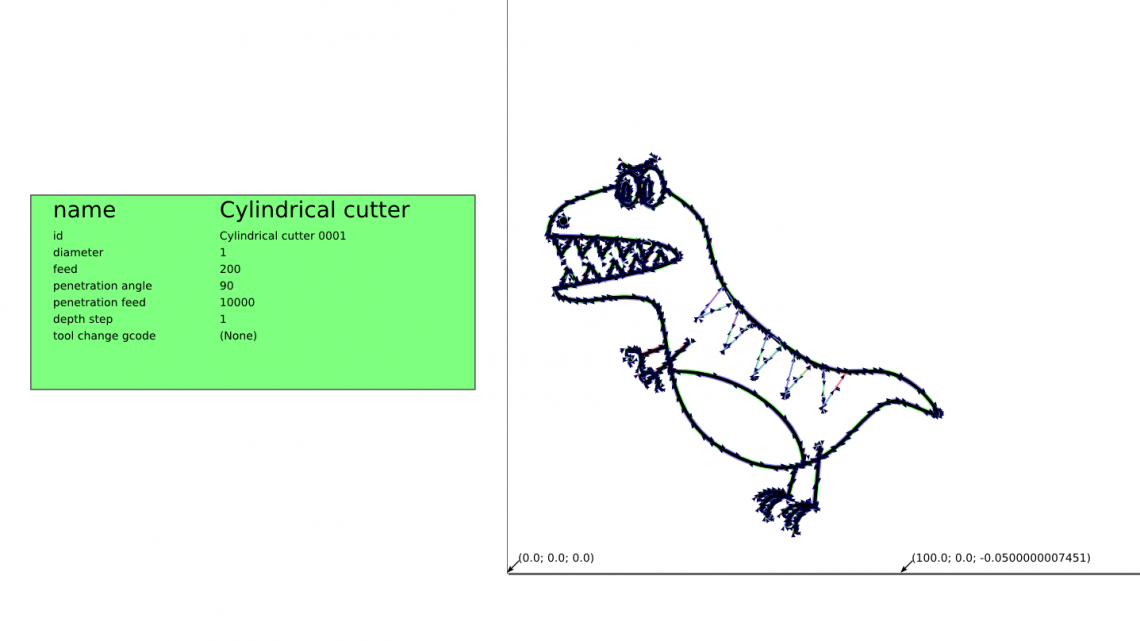

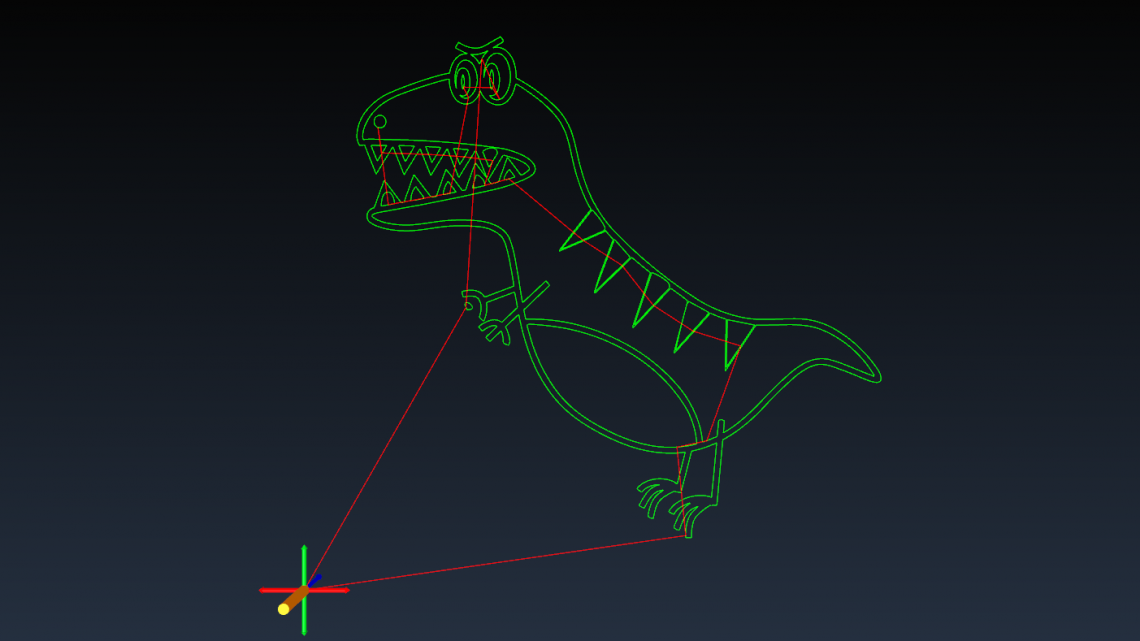

If we don’t encounter any errors, our dino will look like this after the generation process is done:

Visualize the G-code

To confirm that the newly generated G-code will result in something that looks remotely like our dino, we need something to visualize the G-code. There are probably many programs out there which can do this, but we like to use OpenSCAM. Here we can see how long it takes to perform the whole job as well as see how the machine will travel along the path in real or accelerated time.

If you want to have a look at the G-code file, it’s available here.

February 3rd 2018 – Updated with how you acquire the extension (it is now included in Inkscape by default).